Raymond’s origins as a dry community

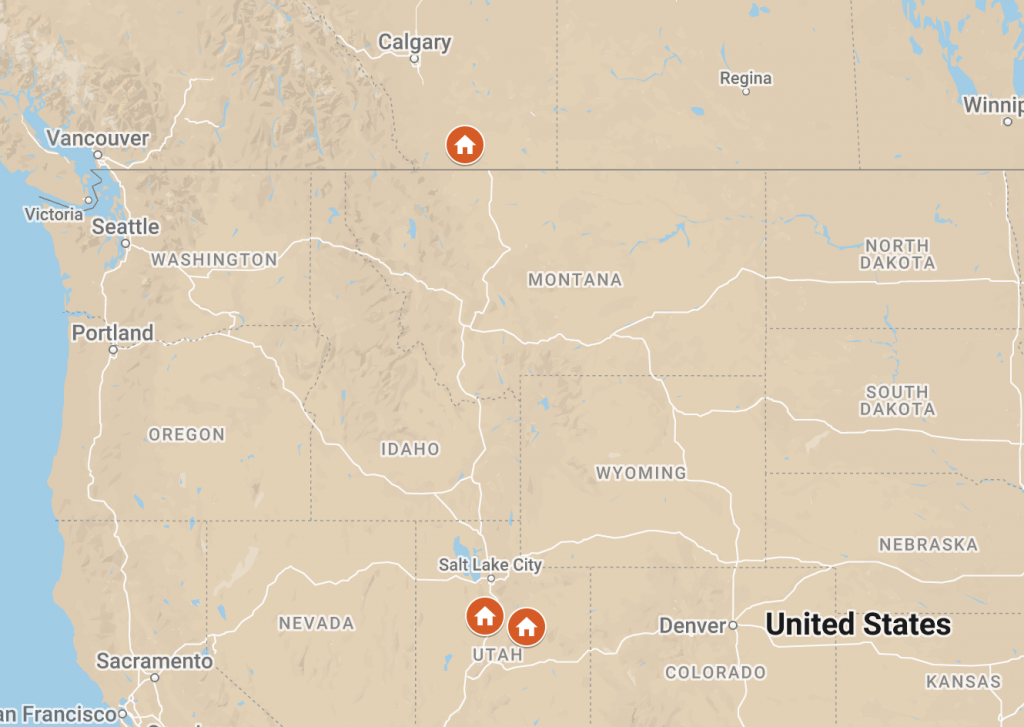

Knightville (aka Knightsville), Utah; Spring Canyon (aka Storrs), Utah; and Raymond, Alberta, Canada all owe their existence to Jesse Knight. Knight was a wealthy miner/industrialist from Utah and a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Though he used different methods to achieve it, all three settlements were established as dry communities where the sale of alcohol was prohibited. Though Knightville and Spring Canyon are now abandoned settlements, Raymond is a town with approximately 4000 residents. Raymond still has in place some of the controls that Knight established in an effort to create a community free of vices such as alcohol and prostitution. Knight was motivated by his religious convictions and his belief that his wealth was the result of divine providence. This led him to feel a responsibility to ensure that his money was not used in pursuits that ran counter to the teachings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The three communities Knight established were each founded as a side effect of his business ventures. Both Knightville and Spring Canyon were related to mining ventures in Utah. Raymond developed as a result of Knight’s establishment of a sugar factory in Canada. Gary Fuller Reese described Knight’s community-building methods as “paternalistic.”1 According to Reese, Knight had seen the vices that plagued many mining communities and wanted to avoid them in the communities which he developed. His efforts were not limited to the sale and consumption of alcohol. In Raymond, he also restricted prostitution and other “immoral” or illegal activities.2

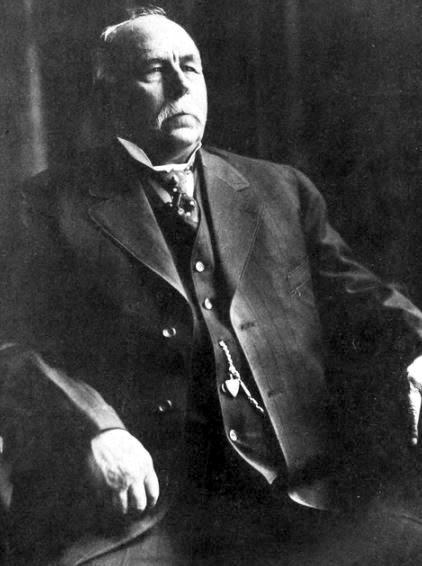

To understand Jesse Knight’s motivation, it is important to have some context from his life. Though the Knight family’s association with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints dated back almost to its founding, Jesse Knight had not always been a practicing member of the church, nor was he born into wealth. Knight believed he was led to his fortune by a voice from heaven. According to his son, J. William Knight, one day Jesse Knight was prospecting in Utah when he sat down by a tree and heard a voice. He told his son that, “we are going to have all the money that we want as soon as we are in a position to handle it properly … I have never had any [impression] come to me with greater force.”6 In 1896 he found the ore deposit that would make him rich. J. William Knight said as soon as his father made the discovery he remarked, “I have done the last day’s work that I ever expect to do … I expect to give employment and make labor from now on for other people.”7 Knight felt his money was divinely appointed to him and came with a “responsibility for doing good and building up the church.”8 His feeling of stewardship was strengthened and clarified when the presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent the following message to members of their church:

Men and women of wealth, use your riches to give employment to the laborer! Take the idle from the crowded centers of population and place them on the unfilled areas that await the hand of industry. Unlock your vaults, unloose your purses, and embark in enterprises that will give work to the unemployed, and relieve the wretchedness that leads to the vice and crime which curse your great cities, and that poison the moral atmosphere around you. Make others happy, and you will be happy yourselves.9

Knight carried this printed message with him in his pocket and would refer to it when questioned on his motivation.10 His efforts to keep the communities he founded from vice was certainly a result of his sense of stewardship but may have also come from his own experience. It seems Knight was familiar with the vices he aimed to protect people from. He shared with Charles A. Magrath that he had at one point frequented saloons, played cards and drank “intoxicants” but that he had had some personal experiences that led him to stop.11 By the time he was developing communities, he was a devout and practicing Latter-day Saint and felt a responsibility to use his wealth to help others avoid vices he viewed as dangerous and opposed to “the church.”

Raymond is distinct from the other two communities because it is still populated and continues to have legal restrictions against the sale of alcohol. As a result, this paper will start by examining how Knight accomplished prohibition in Spring Canyon and Knightville before moving on to Raymond. Knightville was established as a mining town in Utah County, Utah in 1896.12 In Knightville, prohibition came in the form of an employment contract. Knight made several concessions to promote a good workplace including regular wage increases and fewer fees on employee’s cheques in exchange for the allowance from his employees that he could, “summarily discharge men who were found spending their wages for drink and neglecting to support their families.”8 Knight’s biography claims that Knightville was, “perhaps the only mining camp at that time in the United States where saloons did not exist.”13 In Spring Canyon, which was founded in 1912, the Knight’s companies owned all the land and “refused to sell or lease any property for any purpose they felt undesirable.”14 In both cases, the method used to establish prohibition required the continued involvement of the Knights in the community and their continued desire to maintain prohibition. Over 100 years after the exit of the Knight companies and Jesse Knight’s investments from Raymond, prohibition continued because it was legally bundled into each land purchase.

In 1901, Knight founded the community of Raymond. In Raymond, he continued his efforts to establish a vice-free settlement. According to Tycheson Holger, “Knight made sure that everyone understood the town charter, which read that there would be no liquor houses, no gambling houses or places of ill fame established in the town of Raymond, or the property owner would forfeit the title to the land.”15 It was well known at the time that this was required for his involvement in Raymond. The Canadian Parliament’s Select Standing Committee on Agriculture and Colonization met in Ottawa on March 11, 1902. Dr. William Saunders provided answers to questions from the Committee Members and some of those questions were about the new settlement being established in Alberta by Jesse Knight. As part of Dr. Saunder’s response to a question about irrigation he included the following:

Mr. Knight is an ardent prohibitionist, and is having clause put in each of his deeds of sale providing that in case of the establishment at any time of any saloon or drinking place upon any of his property, such property shall be forfeited and revert to the original owner.16

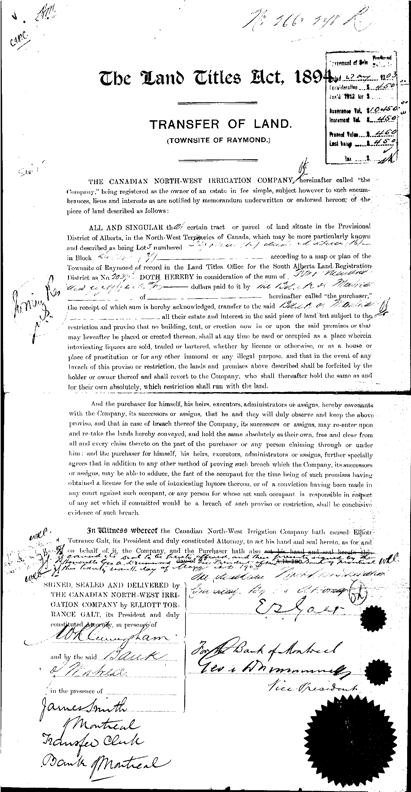

Elizabeth King explained that “[Knight] wished [Raymond] to be, in a sense, a protected sanctuary where families could be reared in [a] religious and wholesome environment.”17 The provisions in the Town charter meant that property purchased in the early days of Raymond had a restrictive covenant registered on title outlining the prohibited activities and an agreement between the purchasers and The Canadian North-West Irrigation Company, who had received the land in this region through a railway land grant.18 The restrictive covenant reads that:

… no building, tent or erection now in or upon the said premises or that may hereafter be placed or erected thereon, shall at any time be used or occupied as a place wherein intoxicating liquors are sold, traded or bartered, whether by license or otherwise, or as a house of place of prostitution or for any other immoral or any illegal purpose, and that in the event of any breach of this proviso or restriction, the lands and premises above described shall be forfeited by the holder or owner thereof and shall revert to the [Canadian North-West Irrigation] Company, who shall thereafter hold the same as and for their own absolutely, which restriction shall run with the land.19

What Knight had established in Raymond was designed to carry forward to new owners of the land and could be enforced regardless of the legality of the activities. As a result of these prohibitions being registered on the purchaser’s title, 120 years later most properties in Raymond still have a restrictive covenant attached to the title. These restrictive covenants remain in place and provide one potential legal hurdle to anyone who would like to open a business that trades in liquor sales. Restrictive covenants are essentially a contract between two or more parties that is registered on the land. As a result, they are not enforceable by the Town or Province unless they are one of the parties named in the covenant. Certainly, there are questions about the enforceability of such a covenant or whether any party would want to enforce them, but to my knowledge, they have never been tested in a court so that remains an open question.

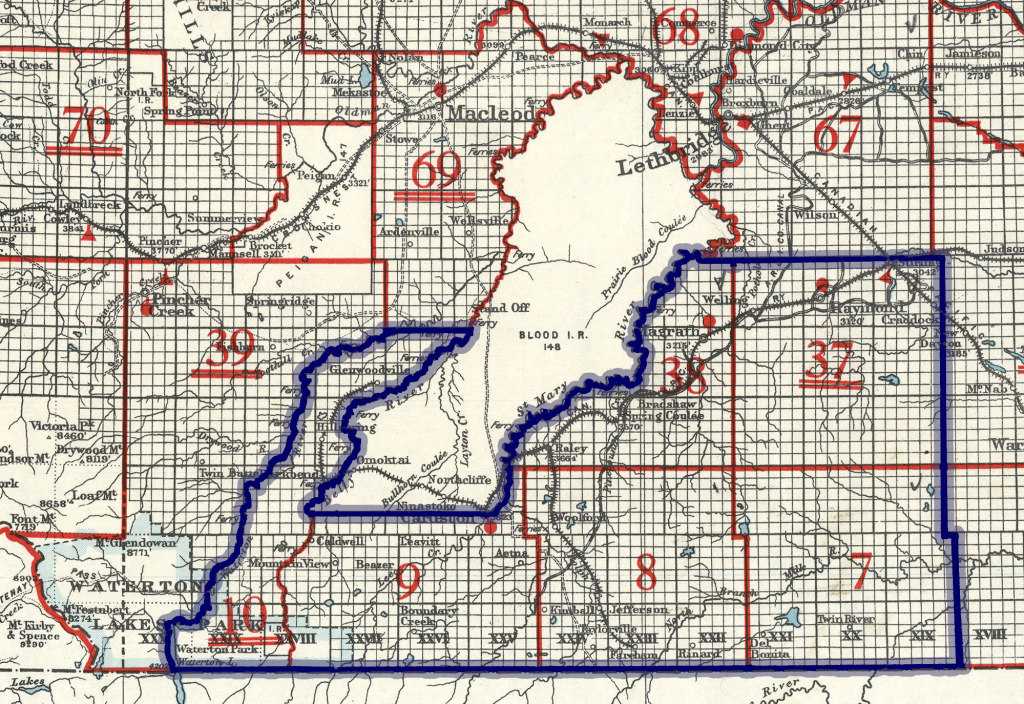

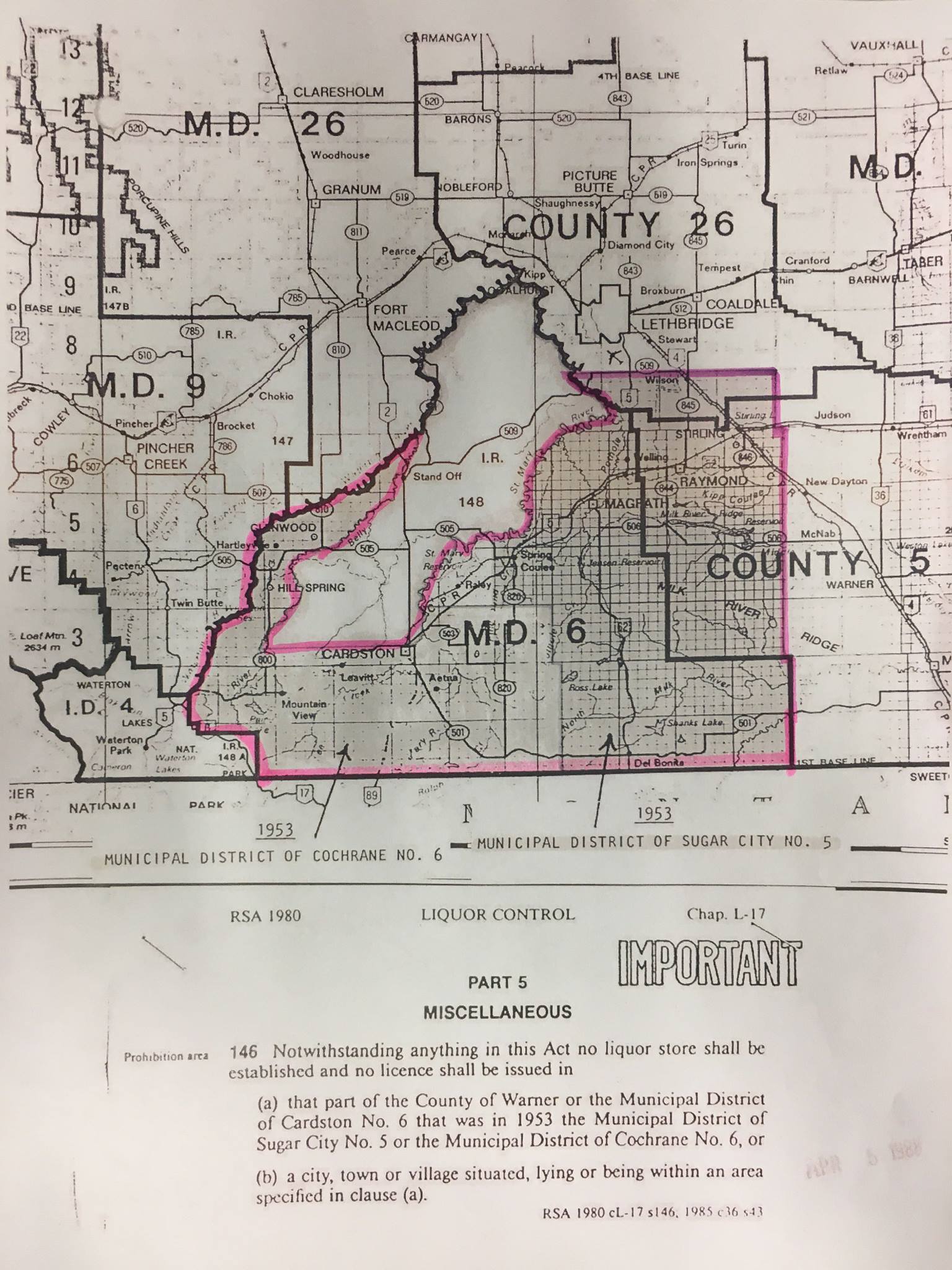

Restrictive covenants have not been the only layer imposing prohibition in Raymond. Up until 2020 restrictions on licensing in Raymond were built into the provincial legislation that governs the sale of liquor across the province of Alberta. Before 1915 the sale of alcohol in Alberta was permitted across the Province except in “local option”20 areas that enforced prohibition at a municipal level. The Cardston license district established prohibition in the region that included Raymond through a plebiscite on June 1, 1902.21 This regional prohibition was already in place when Raymond became a village in July of that same year and there is no evidence of a municipal bylaw enforcing prohibition.22 When provincial prohibition ended in 1923, the legislature debated the act that would govern the reintroduction of liquor sales. The Premier at the time, John Edward Brownlee, argued that a local option needed to remain in the legislation because there had been “an agreement between the Mormon people and the federal government that they should always have the local option right.”23 The Macleod Times listed the Mormon areas as Improvement Districts 7, 8, 9 and 38 and the Municipal Districts of Cochrane No. 10 and Sugar City No. 37.8 These roughly correlate to the modern County of Cardston and a western portion of the County of Warner starting just east of Stirling. The legislation that was passed in 1924 did not explicitly prohibit sales of alcohol in these regions but allowed for local option areas to hold plebiscites to establish prohibition regions. There is no evidence of a local option plebiscite in Raymond or any of the “Mormon area” following the 1924 changes to the liquor act and it seems the plebiscite held in 1902 was sufficient to maintain prohibition.24 When the legislation was revised in 1953 those “Mormon areas” were specifically identified as being prohibited from the sale of alcohol.

135 (2) Notwithstanding any provision of this Act, no liquor store shall be established and no government liquor store shall be established and no beer licence, club licence or other licence to sell beer shall be granted or issued in

(a) Improvement District No. 7,

(b) Improvement District No. 8,

(c) Improvement District No. 9,

(d) Municipal District of Cochrane No. 10,

(e) Municipal District of Sugar City No. 37,

(f) Improvement District No. 38, or(g) a city, town, hamlet or incorporated village situate, lying or being within any of the said districts.25

Those specific regions remain listed in the legislation until that section of the act was removed in 2020 by Bill 2.27 This ensured that between 1953 and 2020, even without restrictive covenants, there was no legal way to get a standing license for liquor sales in the Town of Raymond because of restrictions built into the Provincial liquor act.28 To be clear, these restrictions only applied to the sale of alcohol and not the consumption of it. This layer of prohibition was not directly created by Jesse Knight, but his influence on the principles on which Raymond was founded almost certainly influenced the local desire to remain dry.

Jesse Knight’s efforts to create a community free from alcohol resulted in Knightville, Utah; Spring Canyon (aka Storrs), Utah; and Raymond, Alberta, Canada remaining dry communities for their entire existence. Though Spring Canyon and Knightville are both now abandoned, Raymond is still dry 120-years after it was founded. Knight’s use of land titles was very effective in establishing prohibition in Raymond. Even if the local option restrictions are removed from Raymond, they are still a second potential legal barrier to some properties in Raymond being able to sell liquor.29 Knight’s feeling of stewardship over these communities helped establish the longest-standing prohibition area in Alberta.

- Gary Fuller Reese, “‘Uncle Jesse’ the Story of Jesse Knight Miner, Industrialist, Philanthropist” (Provo, Utah, Brigham Young University, 1961), 26. [↩]

- “Registered Document 1632EK .” (Alberta Government Services Land Titles Office, 1903). [↩]

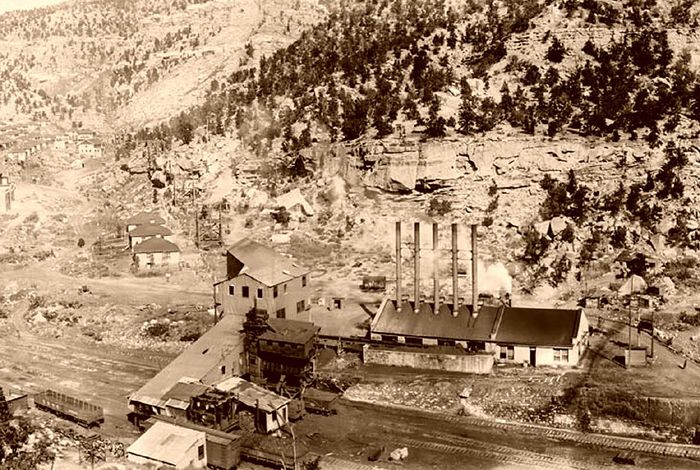

- Photograph of Knightville, accessed April 4, 2022, https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/utah/knightsville/. [↩]

- William Shipler, Photograph of Spring Canyon Coal Company, 1925, 1925, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ut-springcanyontreasure/. [↩]

- Photograph of Raymond, 1960, 1960, http://sites.rootsweb.com/~canwarne/raymond.html. [↩]

- Jesse William Knight, The Jesse Knight Family: Jesse Knight, His Forbears and Family (Deseret News Press, 1940), 39-40. [↩]

- Knight, The Jesse Knight Family, 40. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Ibid, 60. [↩]

- Ibid, 59 [↩]

- Charles A. Magrath, “Knights, Founders of Raymond,” Lethbridge Herald, July 11, 1935. [↩]

- Reese, “‘Uncle Jesse’ the Story of Jesse Knight Miner, Industrialist, Philanthropist”, 26. [↩]

- Knight, The Jesse Knight Family, 44. [↩]

- Reese, “‘Uncle Jesse’ the Story of Jesse Knight Miner, Industrialist, Philanthropist”, 77. [↩]

- Holger B. C. Tychsen, “The History of Raymond, Alberta, Canada” (Logan, Utah, Utah State University, 1969), 30. [↩]

- “Appendix to the Thirty-Seventh Volume of the Journals of the House of Commons, Dominion of Canada,” § Select Standing Committee on Agriculture and Colonization (1902), 19. [↩]

- Golden Jubilee of the Town of Raymond (Raymond, Alberta, Canada, 1951), 3. [↩]

- “Alberta Railway Land Grants.” Department of Geography, University of Alberta, 1990. [↩]

- “Registered Document 1632EK .” Alberta Government Services Land Titles Office, 1903. [↩]

- Local option refers to the situation where a provincial or national legislation is allowed to be overruled locally by popular vote. [↩]

- “Local Option in License Districts,” Lethbridge Herald, February 5, 1908. [↩]

- Raymond’s historic bylaws are accessible online. [↩]

- “Local Option to Stand; No Beer in Dining Cars,” Macleod Times, March 13, 1924, Peel’s Prairie Provinces. [↩]

- I reviewed entries in the Alberta Gazette that listed plebiscites for the years 1924-1928 and found none for any of the “Mormon areas” as defined by Premier Brownlee. I also reviewed newspapers across the Province and found articles about many plebiscites, but none in Raymond or the region around it. The Alberta Gazettes can be viewed online. [↩]

- “Bill No. 81 of 1953,” 1953, https://docs.assembly.ab.ca/LADDAR_files/docs/bills/bill/legislature_12/session_1/19530219_bill-081.pdf. [↩]

- Map of the Province of Alberta (Alberta, Canada: Department of Municipal Affairs Alberta, 1930), https://digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/asset-management/2R3BF1F3BA7L9. [↩]

- “Bill 2 – Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Amendment Act, 2020,” 2020, https://docs.assembly.ab.ca/LADDAR_files/docs/bills/bill/legislature_30/session_2/20200225_bill-002.pdf. [↩]

- The legislation did allow for special event licensing in these areas. [↩]

- Jennifer Dorozio, “One of Alberta’s Last Dry Communities Could Soon See Pours of Alcohol,” News, CBC News, April 1, 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/raymond-alberta-prohibition-alcohol-1.6404684. [↩]

3 responses to “Mr. Knight is an ardent prohibitionist”

I also own a copy of The Jesse Knight Family, and have enjoyed reading it. I was born and raised in Raymond. I’m surprised that the issue of liquor sales in Raymond is a debatable topic because of the reasons you have outlined in this excellent article. I continue to support prohibition in the southern Alberta partly because of Jesse Knights inspired declaration and also because of my personal belief in the evils and despair surrounding every aspect of alcohol consumption.

Dennis Stone.

Excellent job! You’ve condensed so much information so well! I’m crossing my fingers Raymond can continue being unique and that history can be preserved!

Thank you for compiling this interesting information! I too hope Raymond stays unique and special just the way it is!